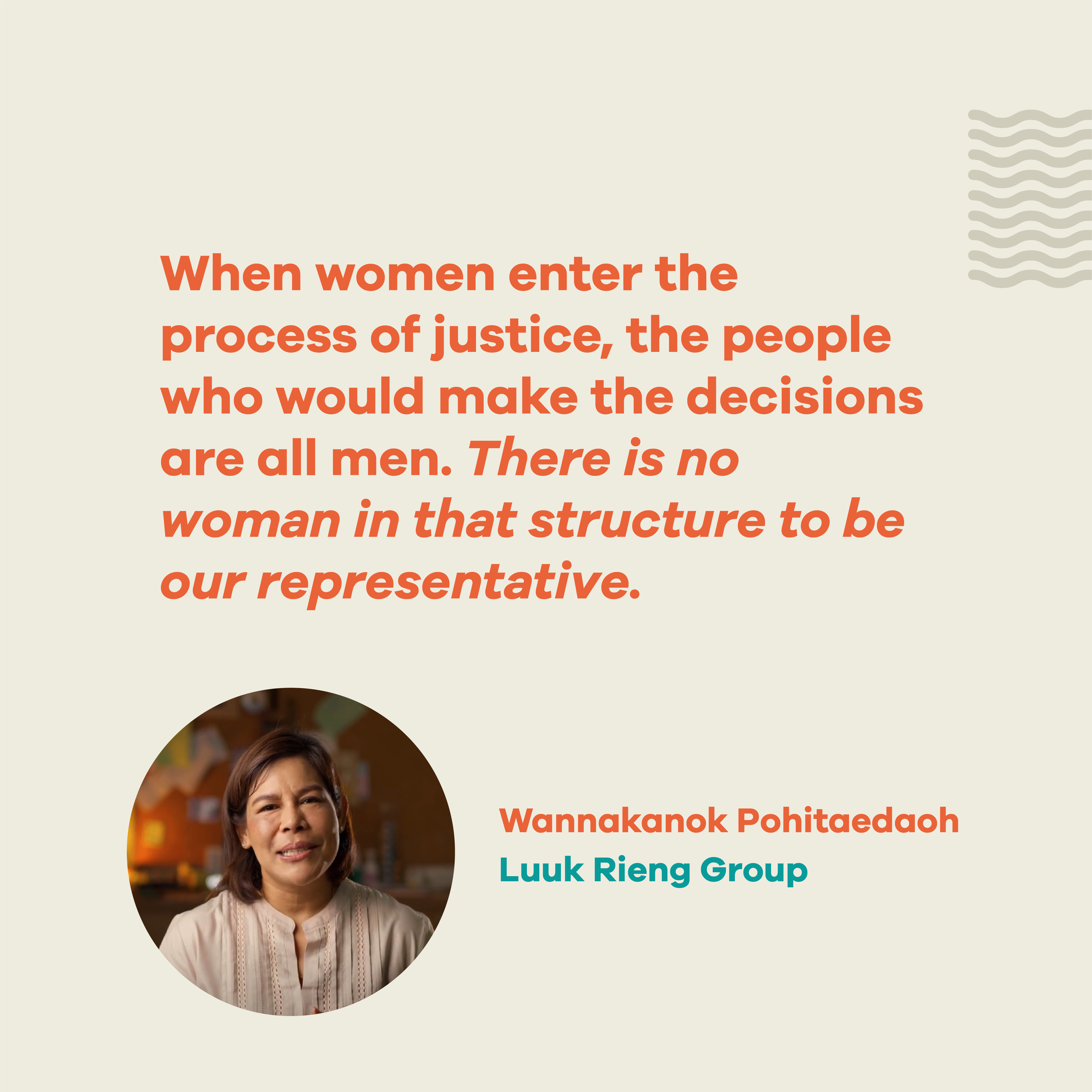

Systemic changes necessary to dismantle barriers against women’s leadership

It is a reality that is evident in workplaces and organizations, one that is often silently shared by women. Even with growing awareness of gender equality and gender bias across the world, women still struggle to be heard and to take on leadership positions, even if they possess the character and skills to perform the job.